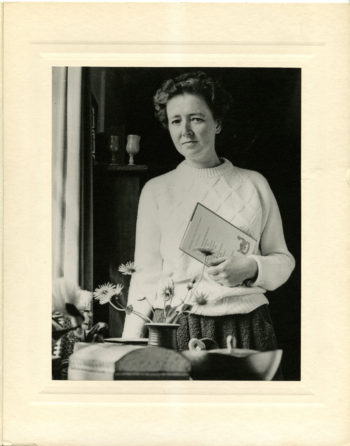

Dana Gioia tiene un artículo iluminador sobre la (tanto conocida como desconocida) poeta Elizabeth Jennings. Allí cuenta un poco de su biografía: Aclamada poeta en Oxford (aunque fugazmente), amiga cercana de la hija de Tolkien, reconvertida al Catolicismo tras un viaje a Roma que pudo pagar con un premio de poesía, y posteriormente víctima del alcohol, drogas, hospitalizaciones. Y a pesar de los pesares, Gioia resalta esto en su artículo, su fe no dejó de ser el gran centro de su vida y su poesía. "My Roman Catholic religion and my poems are the most important things in my life", escribió Jennings en una introducción a su propia poesía.

Y Gioia añade:

Jennings is the poet of quotidian spirituality—a real woman living in real places touched by divine grace. Her religious sense was never detached from her physical senses. Her adult reawakening occurred in Rome, where Christian history took material shape in churches and shrines. The sacred spaces spoke to her soul. Her renewed faith was never fussy and self-dramatizing but a quiet and joyful return to her core identity. One anecdote from her time in Rome illustrates her commonsensical approach. As she climbed the Scala Santa on her knees, Jennings remembered a skeptical priest who doubted that the ancient steps were actually the stairs from Pontius Pilate’s praetorium, which Christ had mounted to stand trial. It didn’t matter, she decided; authentic or not, the shrine was “hallowed by centuries of penitence.”

|

| ("The Life and Mystery of Poet Elizabeth Jennings") |

MY GRANDMOTHER

She kept an antique shop – or it kept her.Among Apostle spoons and Bristol glass,

The faded silks, the heavy furniture,

She watched her own reflection in the brass

Salvers and silver bowls, as if to prove

Polish was all, there was no need of love.And I remember how I once refused

To go out with her, since I was afraid.

It was perhaps a wish not to be used

Like antique objects. Though she never said

That she was hurt, I still could feel the guilt

Of that refusal, guessing how she felt.Later, too frail to keep a shop, she put

All her best things in one long, narrow room.

The place smelt old, of things too long kept shut,

The smell of absences where shadows come

That can’t be polished. There was nothing then

To give her own reflection back again.And when she died I felt no grief at all,

Only the guilt of what I once refused.

I walked into her room among the tall

Sideboards and cupboards – things she never used

But needed: and no finger-marks were there,

Only the new dust falling through the air.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario